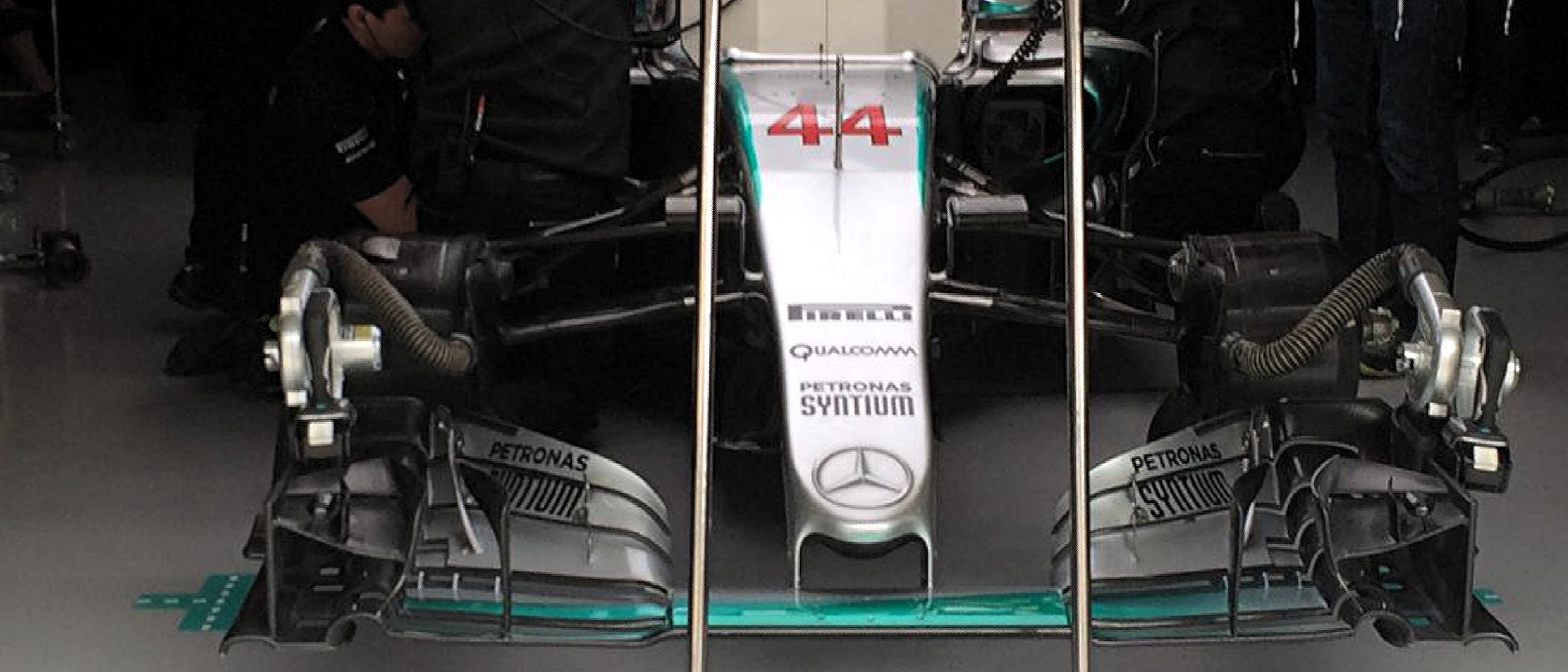

This is an insider’s view of the new Mercedes front wing on the W06 car debuting in China last weekend, courtesy of BBC Radio 5 Live’s track walk reporter. The level of complexity is astonishing. Yet it represents a trend in Formula One that is very troubling.

New @MercedesAMGF1 front wing #f1 pic.twitter.com/eBEnfD4sWB

— Jennie Gow (@JennieGow) April 10, 2015

These days aerodynamics rule F1 no steroids. More and more money is being spent by teams on computer simulations and wind-tunnel tests. There may actually be some good reasons behind Red Bull team principal Christian Horner’s call for limits on wind tunnels. Christian Horner’s plan for a wind tunnel ban is foolish | Ferrari. On the other hand, the prominence of aerodynamics is a direct consequence of rigid design specifications that have fundamentally transformed F1 — from a relatively free engineering laboratory (but see the ill-fated double suspension Lotus 88 and six-wheeled Tyrrell P34) into one where the boundaries for innovation are incredibly narrow. Listen to Craig Scarborough for a sense of how much engineering goes into that new Mercedes front wing:

Combined with transparent gimmicks like double-points — let alone reserving grid passes for “celebrities or really glamorous ladies” — ridiculous penalties for racing incidents, general ban on in-season testing plus strictly limited preseason test opportunities, the product is racing weekends that instead are largely development sessions. Friday’s FP1 and FP2 “practice” periods have morphed into shake-down runs, component test laps and tire degradation data collection instead of competition. Most drivers are eligible for only three to five hot laps during “knock out” qualifying; in the past, of course, the fastest lap in an hour-long qualifying session is what counted. The idea that banning tests yet adding false drama by segmenting qualifying creates a more competitive race is absurd. What it results in is a grid on which faster cars and drivers often end up back in the pack, and frequently as a penalty for aggressive driving. That makes for some wicked first-lap histrionics — and massive shunts like Spa in 2012 — but not more exciting or interesting racing.

There is sadly so much in current Formula One that is about “the show” rather than genuine motor racing.

Formula One is sick.

That is not some wild claim about the state of Formula One. Instead, it has come from the mouth of the man in charge.

In an official interview on the official Formula One web site, Bernie Ecclestone was emphatic about the state that grand prix racing was in right now.

“Sick for a start,” he said last weekend about the condition of the patient. “We have lost audience and I want to know why.”

He is not the only one worried by what has become of Formula One. Even those at its very heart appear embarrassed by what they are seeing.

When speaking to the media at McLaren’s regular Saturday afternoon press gathering in Malaysia, Alonso was hesitant when asked for his opinion on what he had made of watching the Australian GP at home. He paused for a second before a smile spread across his face as he brought the event to an end: “Probably I cannot tell the truth!”

SAVING OUR FORMULA Why we’re #SavingF1….

Yes, F1 is sick. It is sick because it has lost its soul and its purpose. Formula One cannot compete, let alone retain its charisma as the pinnacle of automobile racing, if everything is forced into homogeneity. And as David Coulthard observed, its current obsession with green technology — plus the corresponding cost consequences —suggests the sport is “trying too hard to save the planet.”

Ferrari, McLaren, Williams and other teams from F1’s pantheon of greats have opted into a perverted form of the sport where each constructor builds its version of the same rule-mandated car. Fixed engine specs have F1 manufacturers casting paint-by-number mills with the same 1.6-liter displacement, six cylinders, 24 valves, 90-degree Vs, and central exhaust location. Silly maximum fuel-flow rates, instituted as a nod to environmental concerns, and a 15,000-rpm rev limit, far lower than engine speeds of a decade ago, are made worse by a “token” system for in-season engine improvements and testing bans. Combine that with restrictive chassis and bodywork dimensions, and you have “the once-proud sport of kings reduced to little more than clone wars.”

Having lived through F1’s engineering heights, I can’t help but wonder if a kid building a Soap Box Derby car has more latitude for expression than his grand-prix counterparts. It’s technical asphyxiation.

The real problem with Formula 1 | Road & Track.

It is almost impossible to track how many rule changes have come and gone in Formula One over recent seasons. Refueling and traction control in and out. Wing and nose sizes big and small, high and low. Brake bias only manually adjusted, but then electronic-assisted rear braking systems allowed. Suddenly tires degrade faster, other seasons graining is not an issue. Double diffusers, blown diffusers, flexible front wings, fuel flow sensors, “keel noses,” bargeboards, engine mapping, “Coanda exhausts,” radio coaching, “one move” blocking, “track limits” violations? We do not know. F1 suffers from a persistent form of OCD about change. Everything must always be different.

Take the current technical rules requiring minimum longevity for engines (“power units”) and other key components. Intended to control costs, much like prohibiting spare cars and qualifying tires, these regulations instead place a huge premium on aerodynamics, the principal remaining area — other than pure horsepower — where teams can differentiate themselves. And because the rewards from better aero design are so large, every season is one long exercise in constant, race-by-race modifications and “updates.” Of which today’s in-fashion fads are the “S-Duct” and the “Y250 vortex.”

Take the current technical rules requiring minimum longevity for engines (“power units”) and other key components. Intended to control costs, much like prohibiting spare cars and qualifying tires, these regulations instead place a huge premium on aerodynamics, the principal remaining area — other than pure horsepower — where teams can differentiate themselves. And because the rewards from better aero design are so large, every season is one long exercise in constant, race-by-race modifications and “updates.” Of which today’s in-fashion fads are the “S-Duct” and the “Y250 vortex.”

Yet these things require massive resources. And so, as most things go with F1, it comes down to money. Money which is controlled largely by Bernie Ecclestone under the Concorde Agreement (and controversial, private private side deals Ecclestone has entered into in recent years with Ferrari, Red Bull and other major teams) and heavily weighted towards the larger and more well-financed organizations. As Lotus F1 Team majority owner Gérard Lopez said:

“The distribution model of revenues is completely wrong. When you get teams that receive more money just for showing up than teams spend in a whole season, then something is entirely wrong with the whole system.”

Indeed, in a rare moment of frankness, Bernie himself admitted last fall:

“I know what’s wrong but don’t know how to fix it. No one is prepared to do anything about it because they can’t. The regulations have tied us up. The trouble with lots of regulations and lots of contracts is that we don’t think long-term.”

Bernie Ecclestone admits F1 is in deep crisis and needs help | The Guardian.

This observer tends to agree with The Guardian’s Richard WIlliams.

Since Ecclestone took control of the sport’s commercial rights, he has been allowed to run the whole show. The races take place where he wants, when he wants, under regulations in which he has a large say. So he can endorse an endless list of gimmicks, such as the award of double the normal championship points to the winner of [the 2014] season’s concluding round, conveniently relocated from Brazil to Abu Dhabi, whose rulers can easily afford any premium for the prestige of hosting a stage-managed grand climax on top of the gigantic fee they already pay Ecclestone.

When the man who takes the profit is allowed to make the rules, it is not surprising that a preoccupation with spectacle eats away at the soul of a sport.

Money makes Bernie Ecclestone’s F1 world go round | Richard Williams | The Guardian.

Of course, this is the sport where “we don’t talk about money,” according to Ecclestone. Yeah, right. And F1 fans still believe in Santa Clause.